By David Snowball

I’ll tell you about the six smart guys. They represent a bit over half of the interviews and discussions I participated in during Morningstar’s annual Fest at the McCormick. My normal schedule mixed one-on-one interactions with sitting in on panels and keynote presentations; the changing emphasis of the conference, rather away from hearing from mutual fund managers and strategists, and toward the business concerns of the advisors, led me to focus exclusively on talking with interesting folks.

Many of these interviews will serve as the seedbeds for upcoming fund profiles. In particular, we hope to celebrate the one-year anniversaries of Moerus Worldwide Value (MOWNX), Centerstone Investors (CETAX) and Matthews Asia Credit Opportunities (MRCDX) with full write-ups in the near future. Stay tuned!

Satya Patel: The jumbo shrimp problem all over again

Satya Patel co-manages, with Teresa Kong, Matthews Asia Credit Opportunities Fund (MCRDX). The fund passed its first anniversary on April 29, 2017. The fund’s objective is total return. Over its first full year of operation, it pretty much squashed its “world bond” peer group which is not a particularly representative bunch. By way of illustration, 50% of the fund’s assets are invested in three countries: Singapore, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. For the average world bond fund those same countries occupy 0.50% of assets.

As we noted in our April 2016 Launch Alert, the fund

“invests primarily in dollar-denominated Asian credit securities. The fund’s managers want their returns driven by security selection rather than the vagaries of the international currency market. And so “credit” excludes all local currency bonds. At least 80% of the portfolio will be invested in traditional sorts of credit securities – mostly “sub-investment grade securities” – while up to 20% might be placed in convertibles or hybrid securities.”

We noted four facts that stand out about the fund: the managers are really good; the fund’s targets are reasonable and clearly expressed; their opportunity set is substantial and attractive; and the fund’s returns are independent of the Fed.

The highlights of our conversation:

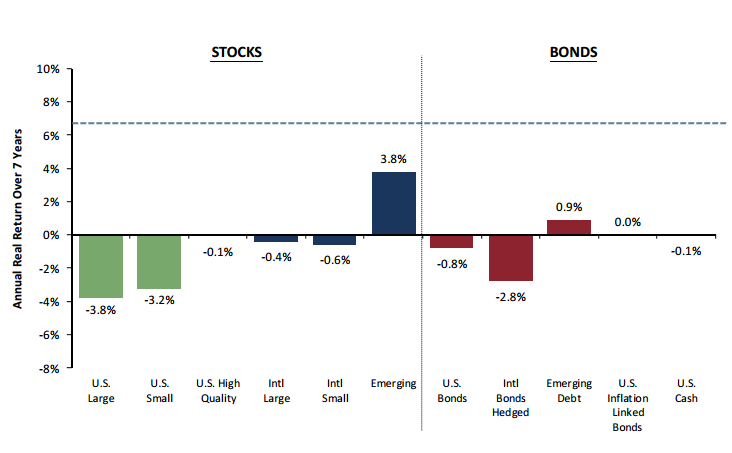

- The fund is plagued by the “jumbo shrimp” problem. Investors immediately think “safety” when they think about fixed income investments and “risk” when they think about Asian investments. As a result, investors seem blinded to the reality that Asian fixed income investments can be both more rewarding and less volatile than their American counterparts.

- If you’re willing to look at a U.S. high yield bond fund, you should look here first. Asian high-yield and credit opportunity investments have a long track record and, in particular, a long record of offering higher returns with lower volatility than US high-yield. The same thing is true of EM bonds; the Asian products simply and consistently outperform the global EM bond markets.

- They’re not concerned about asset levels. Ms. Kong at one point observed that “we might be five years early in launching this fund, but that’s not a problem for us.” Mr. Patel concurred, observing that when investors finally come to value Asian fixed income opportunities, they’ll be there with a tested product and a clear track record.

Abhay Deshpande: Look West, young man.

Also East. But especially West. Especially if Europe is in that direction.

Abhay Deshpande manages Centerstone Investors (CETAX) and Centerstone International after seven years at the helm of First Eagle Global, Overseas and U.S. Value. The funds passed their first anniversary on May 3, 2016. The fund essentially matched the performance of its “world allocation” peer group and of its progenitor, First Eagle Global (SGENX).

As Mr. Deshpande noted for our June 1, 2016 Launch Alert,

“we hope to address a significant need for investment strategies that effectively seek to manage risk and utilize active reserve management in an effort to preserve value for investors,” says Mr. Deshpande. “It’s our intention to manage Centerstone’s multi-asset strategies in such a way that they can serve as core holdings for patient investors concerned with managing risk.”

The highlights of our conversation:

- The fund’s high cash stake – around 20% – reflects the stretched valuations in the American market. While Mr. Deshpande does not believe that U.S. stocks are in a bubble, their valuation work suggests the market is richly valued. After eight years, “to expect a lot more from this market is to expect another bubble.” While there still are cheap stocks in the U.S. market, most of them “deserve to be cheap.”

- Even “domestic” investors need to move overseas. Both U.S. and non-U.S. stocks tend to have extended periods, say 5-7 years, of market leadership. There is “a large and widening valuation gap” between U.S. and European stocks. That gap is likely to grow since U.S. firms have already surpassed their 2007 earnings peak; European firms are still 25% below peak earnings, as that earnings gap closes, European stocks will become even better-priced.

- Across it all, the fund is managed to protect investors’ capital. Their investment process begins with an assessment of a firm’s risk to invested capital; if they can’t accurately assess the risk, they conclude that the stock isn’t worth owning at any price. If they can assess the risk, they’ll consider buying only at a price that embodies a sufficient margin of safety. They simply don’t feel compelled to be invested just for the sake of being invested.

Jon Angrist: ROME may fall, ROTA won’t

Jon Angrist manages three Cognios Fund. Their flagship is Cognios Market Neutral Large Cap (COGMX). Its two new siblings are Cognios Large Cap Value (COGLX) and Cognios Large Cap Growth (COGGX), which broadly represent the long portions of the flagship portfolios. Both launched in October, 2016.

As we noted in our June 1, 2015 Elevator Talk with Jon,

Cognios argues that most market-neutral managers misconstruct their portfolios. Most managers simply balance their short and long books: if 5% gets invested in an attractively valued car company then another 5% is devoted to shorting an unattractively valued car company. The problem is that an over-priced company might well be more volatile than an underpriced one, which means that the portfolio ceases to be market-neutral. The twist at Cognios, then, is to use quant tools to construct an attractive large cap portfolio while changing the relative sizes of the long and short books to neutralize beta. Cognios Market Neutral Large Cap describes itself as providing a “beta-adjusted market neutral” portfolio.

The highlights of our conversation:

- ROME, which identifies “cheap” stocks, may lag the market for extended periods. ROTA, which identifies high quality ones, rarely does. (Reference profile.) Over the past 15 years, there have been only two extended periods in which “trash” beat quality. 2003 was the first such period, and 2016, beginning at mid-year, was the second. Such inversions are typically much shorter – maybe six months, maybe 15, but rarely more – than the market’s periodic preference for pricey stocks over cheap ones.

- It pays to play the percentages. The “high quality – cheap” strategy doesn’t win all the time, nor does it even win in all the trailing time periods but it does win with considerable consistency. If you look at rolling three-year periods (not 2001-03 then 2004-06 but 01/2001-12/2003, 02/2001 – 01/2004, 03/2001 – 02/2004 and so on) you end up winning 60-80% of the time.

- Market-neutral is most attractive when other assets are least attractive. “Advisors tell me,” Mr. Angrist says, “that they can’t afford to put any more of their clients’ assets into equities but they’re scared to death of the bond market right now. That’s when the ‘pure alpha’ potential of a market-neutral strategy makes the most sense.

Amit Wadhwaney: The amiable “Dr. No.”

Amit Wadhwaney manages Moerus Worldwide Value Fund (MOWNX/MOWIX), which launched on May 31, 2016. The name suggests two of its attributes (global + value). It also tends to be concentrated and rather more focused on absolute value than relative value. That is, they’d much rather hold cash than force themselves into buying “the best of a bad lot.” They’d prefer to buy-and-hold and, if a good holding’s price falls, to buy some more. The fund’s current small- to mid-cap orientation is not intrinsic, it’s just where they’re finding value now. Mr. Wadhwaney managed Third Avenue International Value (TVIVX) from the start of 2002 to the middle of June, 2014. During that time he substantially outperformed his benchmark, turning an initial investment of $10,000 into $31,600 while the international benchmark index would have risen to $26,200.

In our Launch Alert for Moerus Worldwide Value, we noted:

Mr. Wadhwaney chose the Latin word “moerus” because it embodies his investing approach. The moerus was a city’s defensive walls, protection against risks both known and unanticipated. In describing his portfolio, Mr. Wadhwaney reports that “we seek to populate our portfolios with companies that have a ‘Moerus’—the strength, staying power and wherewithal—to withstand a variety of risks.” His mentor, Marty Whitman, employed a similar approach.

The portfolio is built from the bottom up and will generally hold 25-40 names, including firms in the U.S. and the emerging markets. The target is undervalued stocks of firms that have “solid balance sheets, high quality business models and shareholder-friendly management teams.”

Over its first 11 months of existence, MOWIX gained 21.6% (despite a 23% cash position) while its peers rose by just 14.3%.

Our conversation focused mostly around the fund’s emergence and the dramatis personae surrounding it, a chunk of which was both fascinating and off-the-record. (Sorry.) For the record, Mr. Wadhwaney did note that many of the names in the portfolio were companies that he’d been tracking for 5-8 years, but which had never been cheap enough to warrant buying. His preference, he noted, is for “absurdly cheap” equities when he can get them, and cash when he can’t. The Moerus investment team is small (analysts John Mauro and Michael Campagna were present at the creation), but growing (Ian Lapey joined last year) and well-integrated (all of the principles have years of experience working together at Third Avenue Value). Mr. Wadhwaney celebrates in particular Mr. Lapey’s “similar but very different eyes” as an investor. As an illustration, Mr. Lapey was given time before he joined the firm to review the fund’s holdings. At a meeting with the team, he expressed deep reservations about half the portfolio and grudging acceptance of the other half.

Mr. Wadhwaney claims that his basic approach is to look for reasons to reject an investment idea, not to accept it. As to the reference in the title of this piece, he shared the story of a year-end video in which one of his Third Avenue associates, improbably donning a blonde wig to impersonate Mr. Wadhwaney, went through a series of corporate analyses, rejecting each, to the refrain “Amit says ‘no!’”

David Marcus: The “Yeah, But” Syndrome

David Marcus manages Evermore Global Value (EVGBX), a fund whose special-situations emphasis mirrors his training with Michael Price and the folks at the Mutual Series funds. Mr. Marcus’s career has at least three phases: the early years developing the art of investing in companies whose situations were too complicated, too special, for ordinary investors to pursue, the middle years as the private investment manager for a rich Swedish family, and this latest period which allows him to pursue his passions on behalf of his own investors. I’ve been speaking with Mr. Marcus on and off for four years now and he’s consistently among the most engaging and thoughtful people I’ve met.

In our 2014 profile of Evermore Global, written at a time when the fund had one star from Morningstar rather than the five it has now, observes:

The discipline that Max Heine taught to Michael Price, that Michael Price (who consulted on the launch of this fund) taught to David Marcus, and that David Marcus is teaching to his analysts, is highly-specialized, rarely practiced and – over long cycles – very profitable. Mr. Marcus, who has been described as the best and brightest of Price’s protégés, has attracted serious money from professional investors. That suggests that looking beyond the stars might well be in order here.

The highlights of our conversation:

- Europe continues to drive the portfolio for now. Nearly 70% of his investments are in Europe, which continues to import lots of U.S.-style activism that has the potential to unlock the value in ossified corporations.

- Asia is rising fast as an area of interest. Asian governments, Japan in particular, have been making a series of legal and regulatory reforms that reward responsible corporate behavior. Some corporations, such as Panasonic, have accepted the challenge, trimmed dead-end divisions and focused on areas where they have strong competitive advantages. Very few managers have yet followed, but the process of change is evident especially in smaller-cap companies. It will only take a handful of brave managers to produce enough change for the fund to benefit handsomely from it. Mr. Marcus, who enjoys baseball metaphors, believes “we’re still in the pregame warmups” for Asia but in the middle innings in Europe.

- Exposure to the US market is at historic lows as prices continue to rise and the opportunity set continues to fall. “Look at my cash position,” he notes. “That’s the money that we would have put into the U.S. if opportunities were available.”

- He has challenged his team and himself to think more broadly about the risks in their portfolio. He’s interested in sussing out two sorts of risk in particular: those poses by disruptive change and those operating at one remove. The first set of risks is pretty straightforward: from drones and augmented reality to 3D printers large enough to print a small house, new technologies are being commercialized at an astounding rate. What effect might such rapid changes have in the next three years to, say, Bollore SA’s freight-forwarding business or to Codere’s profits from gaming and amusement parks? The second set of risks is those faced not by the company in which you invest, but in the companies with whom your portfolio companies compete and cooperate. The fact that your company doesn’t do much business with China is cold comfort if all of its three major suppliers

His particular passion is for rooting out the “yeah, but …” syndrome. “Yeah, but” occurs when an investor becomes too vested in an investment idea and begins making excuses when the original rationale for owning a firm begins to implode.

We bought this dog because they were going to spin off their buggy whip division in a separate firm, eliminating a major drain on earnings. Instead, they’ve decided to pour more money into it.

Yeah, but … we couldn’t have foreseen the new Bluetooth-enabled buggy whips which will allow users to link it directly to their wifi-enabled beer kegs!

Thirty seconds after you resort to “but,” Mr. Marcus concludes, it’s time to sell. As a service to all of the folks at Evermore, we’d like to introduce them to Daan Roosegaarde, the Danish creature of the “yes, but…” chair. As a time-saving convenience, and to save Mr. Marcus’s voice, the chair simply delivers a (mild, so far) electric shock whenever it hears the phrase “yes, but.”

You’re welcome.

Abhi Patwardhan: 32 and counting!

Abhi Patwardhan co-manages FPA New Income (FPNIX) with Tom Atteberrry, who’s been on the job since 2004. It seems likely that, as part of a larger generational change, Mr. Padwardhan might become lead manager of the $5 billion fund in the not-too-distant future.

FPNIX is a bit outside our normal coverage universe, but I enjoyed the opportunity to share a hallway conversation and a bit of time over a small group dinner with Mr. Patwardhan. He comes across as a very impressive young man, sharp, thoughtful and full of detail about his fund’s holdings and their profiles. I learned, for example, rather a lot about Aviation Equipment Trust Certificates and the special joy of buying busted certificates at 28 cents on the dollar with an effective yield of 9.5%. Really, it was cool.

The fund has two objectives: post a positive return every single year (currently the streak is at 33 years, ever since FPA took over management) and to produce returns 100 bps above inflation every year (which, in recent years, has been harder for them to achieve). Given the fund’s (and FPA’s) focus on absolute returns and protecting investors’ capital, it’s not surprising that they’ve been stress-testing every portfolio holding by stimulating its returns assuming a 100 basis point rise in interest rates over the next year. Anyone who doesn’t have a positive return over that period has been shown the exit.

In general, the managers are skeptical about the state of the bond market which has led them to hold rather more cash than normal and to maintain rather shorter durations than is typical. On whole, I came away thinking that the fund was good and in good hands.

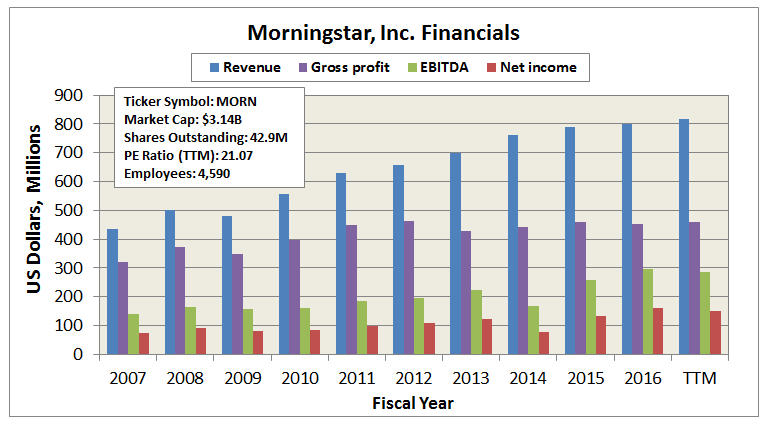

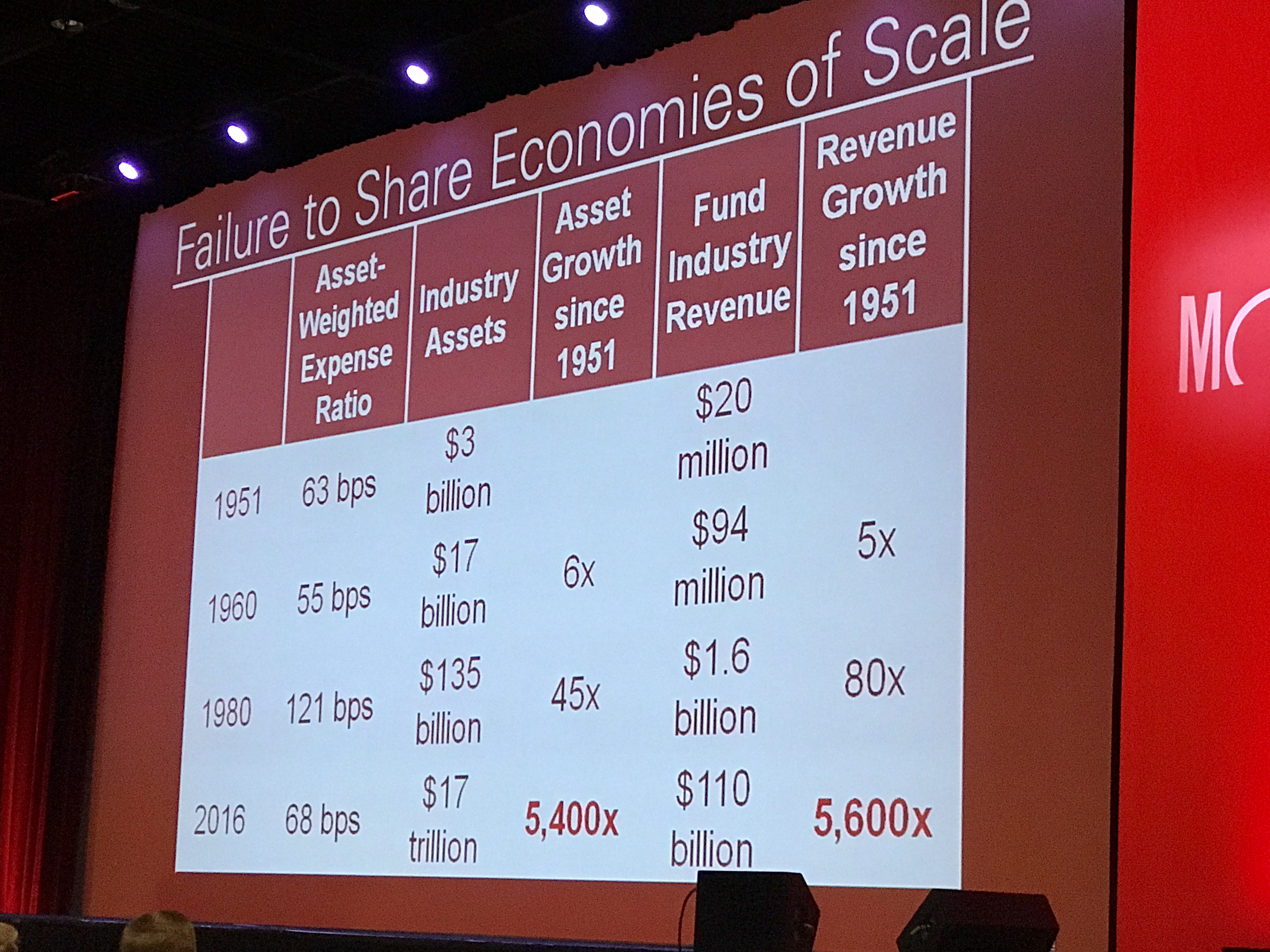

Ken Gallaway: As with judo, it’s all about leverage

I spoke briefly with Mr. Gallaway who heads Morningstar’s global manager research effort. His perception is that Morningstar was Balkanized, possessing lots of operating units with lots of autonomy and rather less coordination (“synergy” in the world of business buzz) than ideal. He’s been on-the-job for 12 months, and much of the focus has been on integrating resources worldwide so that insights or innovations in, for example, the US market get disseminated to the teams in Australia or the U.K. One example of that is the global roll-out of their “Mind the Gap” studies, which look at the losses that investors inflict upon themselves through poor timing and poor decision-making. The calculations are made by looking at detailed fund flow data alongside fund performance data; at base, it asks whether (and under what conditions and to what extent) investors buy high and sell low. They’re not available quite yet.

Scout Funds: “Nah to the ah to the, no, no, no”

On April 20, 2017, UMB announced that it signed an agreement to sell Scout Investments and Reams Asset Management for approximately $172 million in cash to Carillon Tower Adviser, a wholly owned subsidiary of Raymond James. The sale will be completed by year’s end. In announcing its 2016 creation, James described Carillon as “new company to provide transparency and create efficiencies among its asset management firms.”

UMB’s public rationale for the move was that asset management has “limited connectivity with our relationship-based banking model,” and was a sort of distraction from it.

With interest in the sale expressed on our discussion board and representatives from both Scout and Carillon at Morningside, I thought I’d try to learn a bit more about the sale, its rationale and implications.

The Carillon rep was vague, but pleasant. Raymond James had mostly helped with financial support in “the early days,” which seemed an odd for a firm less than two years old. The goal was “to round out our suite of offerings,” which also include the Eagle Asset Management funds. It seemed likely that the products would be rebranded and, on the critical question of fees and expenses, “that it makes sense there would be a unified structure for them.” One possibility is that Eagle would become a no-load family, the other is that Scout would gain (anachronistic) sales loads. No word on when further details would be shared.

When I tried asking folks with the Scout Funds about it, they began channeling their inner Megan Trainor:

I think it’s so cute and I think it’s so sweet

How you let your friends encourage you to try and talk to me

But let me stop you there, oh, before you speak

Nah to the ah to the, no, no, no

My name is no, my sign is no, my number is no

You need to let it go, you need to let it go

Need to let it go.

In an almost cartoonish style, the Scout representative repeated the phrase “no comment on that” five times in two minutes, despite some of the questions bearing on stuff that’s already in the public record.

There are many ways to say “no.” Heck, there was even a collection, The Rhetoric of No (1970), in which famous speeches were organized around the kind of “no” they reflected: the emphatic no, the reflection no and so on. The way we say “no,” indeed the way we say anything, reveals a lot about our view of ourselves and of those around us. Morningstar’s Nadine Youssef did a really nice job, in another conversation, of turning aside queries about Morningstar’s impending lineup of mutual funds; her tone was “I wish we could share more information, but really we legally can’t, and so no.” The Scout representative’s message was more “go away, little man, you’re not getting the time of day out of me.”

Sorry, I don’t have a really gender-neutral alternatives to “big-boy pants.”

Sorry, I don’t have a really gender-neutral alternatives to “big-boy pants.”

Appleseed is one of them. The fund holds a substantial amount of gold (“a hedge in the event of a currency crisis” but also an inflation hedge and a diversifier) and cash, five times more small cap exposure than its peers, and a third more emerging markets exposure (data as of 3/31/17). With 21 positions overall, it’s far more concentrated than its peers and it imposes an ESG screen that eliminates, among other things, banks that are “too big to fail.” It has a low-beta portfolio which has substantially outperformed its Lipper peer group over the full market cycle, but has lagged them over the past 3- and 5-year periods as market valuations continue to climb (and most managers continue to play along with a market in which they have no confidence). Morningstar’s judgment is about right, “Appleseed is tough to classify, but it has plenty to offer the right kind of investor.”

Appleseed is one of them. The fund holds a substantial amount of gold (“a hedge in the event of a currency crisis” but also an inflation hedge and a diversifier) and cash, five times more small cap exposure than its peers, and a third more emerging markets exposure (data as of 3/31/17). With 21 positions overall, it’s far more concentrated than its peers and it imposes an ESG screen that eliminates, among other things, banks that are “too big to fail.” It has a low-beta portfolio which has substantially outperformed its Lipper peer group over the full market cycle, but has lagged them over the past 3- and 5-year periods as market valuations continue to climb (and most managers continue to play along with a market in which they have no confidence). Morningstar’s judgment is about right, “Appleseed is tough to classify, but it has plenty to offer the right kind of investor.” focus on investment rather than management.

focus on investment rather than management.